What is the true, human cost of our cheap clothing? Last week an eight storey garment factory collapsed in Bangladesh killing nearly 400 people, most of them young women. Intense retail competition and demand for ever-cheaper clothing in wealthy nations have fueled the economy of this extremely poor nation, but safety standards for workers are often lacking. In this case, the building owner apparently had permission to construct a five storey structure, but later added three more floors illegally.

At Lipstick and Politics we like to say that everything is political, including our lipstick. This avoidable tragedy is a perfect example of that. Our fashion choices have direct political implications. How many times have we unwittingly patronized a retailer whose goods are manufactured in unsafe conditions and sometimes by children? Worse, how many times do we choose to ignore the working conditions of the people who make our clothes? I certainly have.

The factories housed in the collapsed building supplied garments to various western labels. Two of them — UK discount retailer, Primark and Canadian clothier Loblaw — announced that they would compensate the victims and their families. When I lived in the UK I shopped at Primark. It is super cheap and, hey, sometimes I just didn’t want to spend more than $3 on a T-shirt. The thing is, I have a lot of T-shirts. I have so many T-shirts I don’t even know what T-shirts I own. I have more clothes than I need. I have more “stuff” than I need. Every time I move internationally I have to live out of suitcases for a few months and I realize I don’t need all my material things. Then, the “stuff’’ arrives and I can’t (don’t) get rid of it. This year I moved to India and as my part-time maid helped me unpack, it was clear she thought that I not only had too many clothes, but that I wasn’t taking care of them properly. “They’re too expensive,” she said shaking her head at the pile of clothing that came out of a box and was piled on the floor. She lives in a one-room tenement flat and sleeps on the floor, yet always comes to work beautifully dressed while I poke around the house in yoga pants. She appreciates the value of the things I just toss on the floor.

My grandmothers knew the value of things. They didn’t have closets overflowing with clothes that they didn’t even remember they had because clothing had value in those days. Belongings had value. A coffee can was used for storing tools, a wooden Velveeta box became a pencil holder, socks were darned, jeans were patched…it wasn’t a disposable society. These days it would seem that even the human beings who make our disposable belongings are disposable as well. But that doesn’t have to be the case…

Bryan Walsh writes in Time magazine, “Customers can do their part by putting a little pressure on their favorite brands, though that would require placing as much value on the cost of a life as you might on the cost of a T-shirt.”

In the ‘90s Nike had to change it’s manufacturing practices when it received a spate of bad publicity about it’s manufacturing practices and was successfully sued. It seems likely that Primark and Loblaw are trying to avoid the consumer boycotts that Nike faced. According to this article in the Washington Post, poor countries can keep workers safe and still escape poverty, safety regulations don’t have to add a lot to the final cost of our garments. Selling cheap T-shirts doesn’t mean that garment workers should have to risk their lives to feed their families.

2 comments

Excellent article. Practically, though, how can we monitor the origin of everything we buy? And this tragedy – truly horrid – seems to have been caused by mismanagement. Aren’t all building additions need to be approved by some regulatiry agency in India? Or is it a free for all?

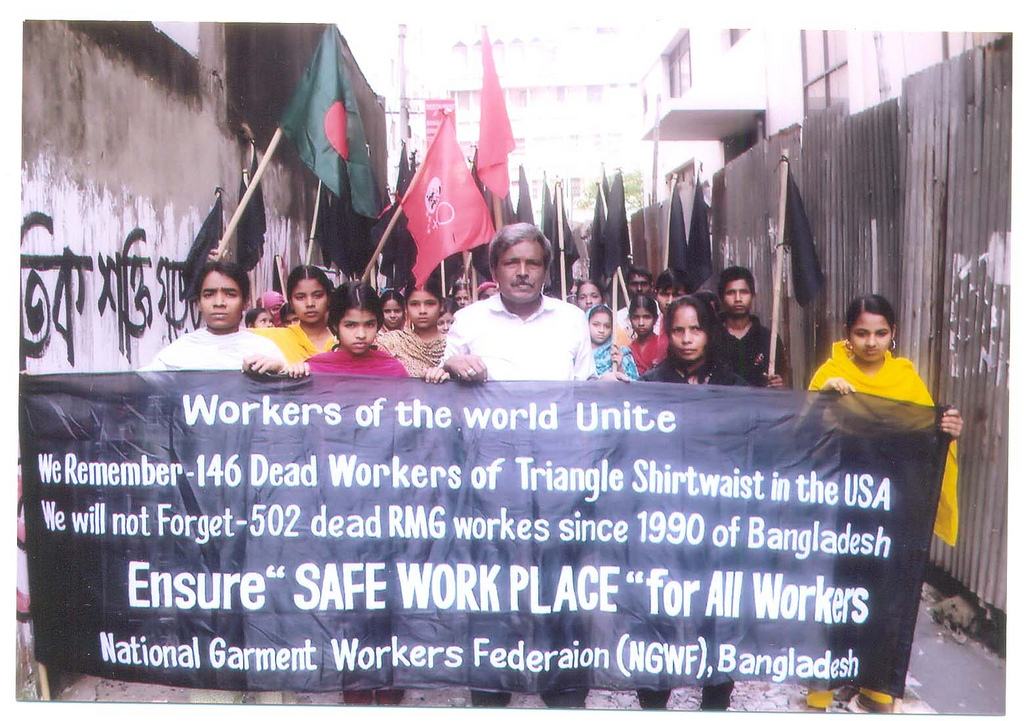

Sasha, I agree that it’s impossible to monitor the origins of everything we buy, but I know that I could do a lot better. For instance, I stopped buying knock-off, fake designer handbags because they are mostly made in sweatshops and violate designers’ IP. I probably could shell out a little more for fair-trade products. This factory collapse was in Bangladesh, not India. It’s a much poorer country, though India has it’s regulatory problems and a lot of corruption as well. I think that the Nike case from the ’90s in a good example. Consumers and consumer groups can ask retailers to improve the standards of the factories they contract with. With social media it’s easier for us to pressure these companies and spread the word. Also, there are probably ways we could support Bangladeshi workers’unions, but that would be another blog.