In our society, women are often looked to for emotional support by everyone else around them. This responsibility is a full-time job. And women are conditioned during their youth to take on this responsibility. Here’s one experience of how this is so.

“I want to say: we come from difference, Jonas, you have been taught to grow out, I have been taught to grow in.” – Lily Myers, “Shrinking Women”

It’s an early spring evening in Montreal, and my boyfriend and I are arguing about feminism on the metro (hello, my life). Today’s politically charged topic that’s highly sensitive to me and mostly only intellectual for my boyfriend (hello, love) is emotional labor.

Like many men I know, my boyfriend claims not to believe in the concept of emotional labor: the feminist idea that women – and other people that society labels “feminine” – are socialized to provide a vast array of emotional services for other people (usually men), most often without acknowledgement or pay.

Common examples include the social practice of random men telling women to smile in public– Why? She isn’t happy to see you; she doesn’t even know you! – the expectation for waitresses and airline hostesses to flirt on the job, and the higher pressure on mothers than fathers to take on the brunt of child-raising duties.

Less commonly discussed, but just as important, examples include the expectation for gay men to play the “gay best friend” character and for trans people to describe the shape of their genitals (answering the “have you had the surgery” question) to anyone who asks.

My boyfriend, though, says that the idea of emotional labor misrepresents the relationship between men and women by placing a monetary value on interactions that are priceless. He says that women give the gift of their love and attention to men, just as men do to women, and trying to compete over who gives more is pointless and creates unnecessary conflict.

(I should give the disclaimer at this point that my boyfriend is a truly wonderful guy, and I love him deeply – partly because he challenges me so much.)

And as we argue, our voices growing louder and louder with both vehemence and to compete with the roar of the metro, I feel myself starting to get—well—emotional.

You see, my boyfriend is a scientist – when we have an argument, he wants logic, facts, and figures. He challenges me to prove that my ideas are empirical, that I have stats to back myself up.

And that isn’t wrong, necessarily.

But I’m an artist, a writer, and social worker, and while emotional labor certainly has been academically studied for years, I tend to understand the world through stories and my personal experiences.

And so he doesn’t understand why, beneath the hard edge of his questioning and the mechanical scream of the metro, I grow visibly upset.

How can I explain to him, prove to him, that what I’m talking about isn’t just some silly feminist idea made up by whining bra-burners? How can I show him why this is important to me, why this is real?

How can I define something that resists definition, that is made up of a million separate moments and unique experiences that ultimately form the shape of my life?

Now I can see him getting uncomfortable. He doesn’t mean to upset me. He doesn’t want to be “that guy” making his girlfriend cry on the metro. I can see the question in his eyes: Why am I putting him in this position?

So I swallow the feelings, push back the memories, sit up straight, and smile. I change the subject. Nobody likes an oversensitive girl.

And privately, in the place in the back of my mind where my stories live, I think about how I learned to do this work of caring for others’ feelings at the expense of mine.

4 Years Old: Resisting Makes It Last Longer

One of my earliest memories – certainly the earliest that I can definitively call emotional labor – is going to visit my grandparents’ house as a small child.

In the memory, my sister and I don’t like going to visit our grandparents, mostly because we’re scared of YehYeh (Toisanese for paternal grandfather).

Whenever we see YehYeh, he picks us up, pull us into his lap, and invasively caresses us for what felt like hours at a time. His yellow-nailed fingers roam everywhere, all over our bodies: face, hair, neck, chest, waist, belly, thighs. I hate it.

His kisses are fat and wet and last much too long. One time, I try to push him away in the middle of a kiss, and he laughs uproariously and holds on tighter. Then he tells my parents.

“So rude and ungrateful,” they scold me. In Chinese families, the worst thing a child can be is ungrateful. “Your grandfather is just showing how much he loves you. Don’t you love your YehYeh?”

“Just let it happen,” my sister, a wise five years old to my less experienced four, advises me. “It’s over faster that way.”

The next time YehYeh pulls me into his lap, I smile and sit still as he strokes and pets and kisses me.

“Lei oingo gum doh di?” He asks me over and over. “How much do you love me?”

“Gum doh di, YehYeh,” I say. “I love you so much, Grandfather. So much.”

Ten Years Old: Love Means Never Saying Anything

My father never talks to anyone about his feelings – except for me, that is.

On long drives, when we’re alone in the car, he rolls down the window and turns up the radio (always the Oldies station that plays the Beatles and Beach Boys and Joni Mitchell in endless loops) and talks to me about everything.

What it was like growing up Chinese in small-town Canada in the 1950s. How hard it was, working in restaurants his whole life from the age of six. Family secrets, like who owes whom money, who had an abortion or a miscarriage, and which relatives spent years in a psychiatric institution. Troubles in my parents’ marriage. Our family’s financial problems.

My father doesn’t ask me what I think about all these things, or if I understand them. I don’t mind.

I know that my job is just to listen, to nod. To hold the weight of these adult things for my father, if only for a little while.

It makes me feel special, listening to these things, even though I sometimes worry about them for weeks afterwards, or have nightmares.

It makes me feel lovable – and loved.

Fourteen Years Old: Take Care of People, Even When You Don’t Know How

My best friend tells me via MSN Online Messenger that she was raped by an adult.

He’s someone close to her, with power over her. He will hurt her if she tries to report him to a teacher, or to the police.

So my best friend can only tell me. I’m terrified, but I know that I can’t make this situation about me. I have to take care of her, the best way that I know how.

I listen. I nod. I hold her as she cries. I rock her back and forth in my arms and tell her that I believe her, that she’s not alone.

I can’t change anything, or protect anyone. I’m just a kid. But this one thing, I can do. It’s the only thing I can.

Sixteen Years Old: Your Feelings Hurt People, So Keep Them to Yourself

I’ve just been released from the psychiatric ward at the local children’s hospital. Forty-eight hours ago, I attempted suicide, which I’m starting to realize is possibly the most selfish thing that I’ve ever done.

That’s what everyone is telling me, anyway.

Once the police brought me into the ward and took the handcuffs off (yep, that’s what happens), someone called my parents in. They both burst into tears when they saw me.

Why was I doing this to them? they kept on asking. Why would I throw away everything they had worked for?

I’d never meant to hurt anyone. I just wanted the pain to stop. Now I know that I have to live, for my parents’ sake. How could I have been so ungrateful?

So now we’re sitting in the car in horrible, awkward silence. My father finally breaks it by telling me that I can’t tell any of our neighbors about “this incident.” It would be bad for the family business.

He reminds me also that I’m scheduled to write the SATS tomorrow, and all of our middle-class acquaintances’ kids will be there. I need to go to keep up appearances. I almost cry, almost laugh, and end up doing neither.

The next day, I put on my game face and go to the SATS. I score in the 95th percentile.

Seventeen Years Old: Love Is Putting Your Needs On Hold

My first boyfriend, who is incidentally a counselor at the camp for at-risk youth I’m attending, has dark purple scars on his wrists. I decide I’d rather not know anything about them, so I don’t ask.

He tells me anyway, though, after he’s snuck me out to the forest to make out under the stars. They’re from the time he tried to kill himself after beating up his girlfriend. He never meant to hurt her, but he couldn’t control himself, and now he’ll feel guilty for the rest of his life. He talks on and on and on, as though he just can’t stop.

All of a sudden, he’s crying uncontrollably and clinging on to me until I almost can’t breathe. I think I should be scared, or exhilarated, or something, but I really don’t know what I’m feeling anymore.

So I revert to what I know best.

I hold him in my arms and rock him back and forth, back and forth. I look up at the stars. Hello, love.

Nineteen Years Old: You Are Only Worth What You Do for Others

I’ve moved across the continent to go to university, and I’ve decided study social work.

I’ve realized that taking care of people is my calling in life: After all, in the past three years I’ve spent in this new town, people have already come to know me as one those nice girls, the ones who are good to talk to.

You know the kind of girl I mean. There’s one in every friend group, a bunch in every community.

The girls who help you stumble home after you spend the night drinking too much. The girls who hold your hand as you cry about the break-up, about your drinking problem, about your fucked-up childhood. The girls you call at 3AM when you’re thinking dark thoughts and you need someone to talk you off the ledge of doing something you’ll regret.

The girls who always seem to end up dating people who need them, because society has taught them that the thing that defines them is taking care of others.

There’s a little of that girl in all of us girls: the girl whose calling in life is to be whatever you need.

Twenty-Four Years Old: A Woman’s Job Is Never Done

I’m sitting in a case conference room at the child psychiatry ward where I’m interning as a Masters student in Clinical Social Work. It’s a big department, and there are about fifty mental health professionals here, half of whom are students.

It’s been five long years of education and training, not to mention life experience, and I’m no longer the wide-eyed, social work-ing idealist I used to be.

I’m drained, exhausted by countless twelve-hour days spent listening to heartbreaking story after heartbreaking story. I’ve broken my own heart many times doing things that I used to tell myself that only bad social workers did, that I’d never do.

I’m tired of trying to love everyone.

As I look around the room, I notice once again that the vast majority of us are women – there are only three men in the whole department. Those men are all doctors or head psychologists, the leaders of the team, the ones who actually get paid decent salaries (as in, about ten times more than the rest of us).

As I scan the faces of all the women in the room – teachers, social workers, nurses, the people who do the grunt work – the hard, deeply underpaid, usually thankless labor of working with mentally ill, often under-privileged children – I see that we all share the same exhausted look.

I wonder how it came to be that so many of us, women, came to join these so-called “feminine” professions. How it is that we were somehow all drawn to this “calling” of caring for others’ minds and health only to end up in impossible working conditions?

Tonight I will go home to my boyfriend after running three therapy sessions in a row and listen to him talk about how difficult his day was at work, how he hates his boss.

Sometimes I try to tell him about my own day at work, but he rarely seems interested.

Twenty-Five Years Old: If You Don’t Help, Nobody Will

I’ve become a very (very) minor Internet celebrity (hello, life) by writing feminist articles and poetry about race, gender, abuse, and mental health.

After publishing a few well-shared pieces, the e-mails start pouring in, from literally all over the world.

Some are from white supremacists and men’s rights activists telling me I’m a stupid, “feminazi,” “ch—k b—ch.” I don’t even read those ones before deleting.

But most of the e-mails are from young women, queer people of color, trans women, asking for advice, for opinions, for friendship. Some of them are even from men, asking me to explain feminist concepts to them.

Sometimes the e-mails are desperate cries for help asking me what to do in situations of intimate partner violence, mental health crises, and suicidal thoughts.

I do my best to help however I’m able. What else is there to do?

***

When I began to write this article, I started out by trying to create a point-by-point, logical analysis of emotional labor and the ways that society teaches us to do it.

But sometimes, the best way to understand something is not try and break it down scientifically, but rather to feel it through the stories that come from our personal experiences, from the unique moments that form the shapes of our lives.

This, I think, is especially true of emotional labor, which is such an effective tool of oppression for the very reason that it occurs in a million tiny ways that are invisible – often even to the person performing it.

Because instead of labor, we’re taught that the work we do to care for others is an act of love which must be given freely, even when it comes at the cost of our own well-being and self-expression.

We’re taught to doubt ourselves, our instincts, our needs, so that we can play the role of loving child, friend, mother, nurse, therapist, lover.

Women and marginalized people are taught, implicitly and explicitly, that part of being who we are is the paradoxical duty to at once understand and care for everyone else’s feelings and desires while not having a right to our own.

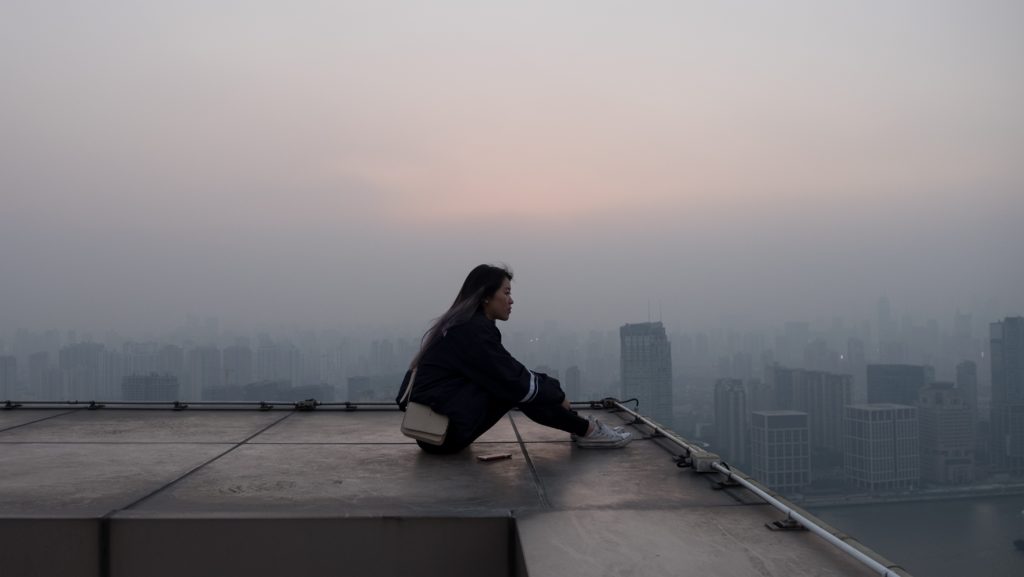

So here we are: sitting on the metro, trying to decide what to do, what to say, what to feel. My boyfriend, unlike some of my boyfriends past, is interested, I think, in knowing how to make things equal between us.

But he doesn’t know what to say. I can see it in his face.

Unlike me, perhaps, he hasn’t been trained from the age of four in the art of listening and making space for others’ voices, doesn’t know how to give up his ideas and his logic and his opinions, his understanding of himself as the expert of anything he puts his mind to.

Unlike him, perhaps, I haven’t been raised to be confident that my ideas mean something, that I might be able to get what I want if I only asked for it, that I ever had a right to ask at all. So he assumed that I didn’t want anything.

I take a breath. I look him in the eye, and smile. I say his name tenderly.

And then I say, “Ask me how I’m feeling.”

Originally published on Everyday Feminism.

Kai Cheng Thom is a Contributing Writer for Everyday Feminism. She is a Chinese trans woman writer, poet, and performance artist based in Montreal. She also holds a Master’s degree in clinical social work, and is working toward creating accessible, politically conscious mental health care for marginalized youth in her community. You can find out more about her work on her website and at Monster Academy.