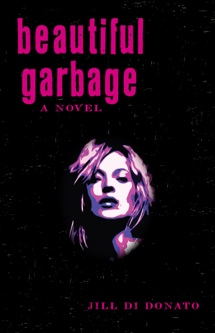

In Beautiful Garbage, Jill Di Donato has penned a vivid, kaleidoscopic story which explores issues of feminine sexuality, creativity, and power, set against the fascinating backdrop the New York art scene in the 80’s. Using tropes of glamor–a word whose etymology suggests something both enchanting and illusory–Di Donato crafts the façade of each of her characters with an eye to what turmoil seethes beneath. There is as much to abhor as admire in the character and life of her protagonist, Jodi Plum, and in the lives of her friends and associates. It is through a reader’s inner conflict that they receive Di Donato’s salient insights and revelations. I had the opportunity to ask the author about her vision and experience with Beautiful Garbage in the exchange that follows.

PM: In your book, New York seems to be its own character, and the art scene you’ve depicted here is full of evocative details. As a New York native, how do you feel the city has shaped your attitude and approach to art, and to your work? In what ways does Jodi exemplify, or perhaps subvert, the familiar narrative of a struggling artist making it in New York?

JDD: As an artist, it’s a wonderful place to work: you can be anonymous like nowhere else; solitary, yet never alone. I was too young to experience the art scene I depict in the book, during the 1980s, when New York had this dangerous desperation. As an artist myself, I’m intrigued by the idea that even in the most wretched situations, beauty of some sort is possible. I think the 80’s was really the apex of the art scene in New York, when all the bohemian artists of the 70’s found their way into galleries, and new artists were being discovered by the great curators of the time, like Mary Boone and Warhol. There was this light bulb that went off, and the commercialism of the scene caught like wild fire. Starving artists, once “discovered,” experienced this decadent lifestyle that we associate with Wall Street of the 1980s.

In my vision, I think it has to do with the desire for the acquisition of beauty, which comes with a high price tag. When the novel opens, in 1984, I think art sales in New York galleries reached something like $1 billion, which was unprecedented and they only continued to skyrocket throughout the decade. We know all about the male artists of this time–mainly Basquiat, Schabel, Haring, Bleckner, Koons–but what about their female contemporaries?

My book pays homage to Lynda Benglis and Alice Neel and then offers a fictional counterpart, Jodi Plum. There are two things that makes Jodi different or subversive for her time. First, she worked in figurative sculpture when abstract art was all the rage (although Neel was a figurative painter), but Jodi Plum uses plaster as her medium, in homage to Greek sculpture. She then takes the idea of being a figurative artist literally and uses her own body as a medium of commerce and expression as a call girl. Second, in her final triumph, she is transparent about the connection between figurative art, which traditionally represents the female form, and money. She literally becomes an “art whore” and is unafraid to present herself that way. It’s that rough honesty that makes up the notion of beautiful garbage.

PM: The novel’s emotional arc involves your interweaving of the past and future in very interesting ways. How much does a woman’s primary relationships (i.e. her mother, her father, her high school friend), as opposed to those she develops later in life (i.e. her agent, her lovers, her peers), guide an artistic career? For Jodi, was the past something she needed to leave or return to?

JDD: When I was writing the novel, I had to ask myself, what would make a person decide to dedicate her life to making art? And then, what would make a woman decide to sell her body and sexuality for money? Basic psychology tells us to look at one’s childhood and family life, so, I wanted to explore the traumas we all have as children to see how they play out in our adult lives.

Jodi takes the break-up of her family, what I call the fallout of the nuclear family, particularly to heart. When her father leaves her and her mother, this abandonment breaks her in a very potent way. She sees herself as undesirable to men and desperate for female companionship. Her teenage friendship with a girl whom she idealizes impacts the way she interacts with women later on in life. She also does some deplorable things as a teenager in an attempt to regain the power she feels she has lost.

As an adult, she’s both reconciling the shame she feels for hurting people as a teenager–and she does commit some pretty detestable atrocities on others–and also trying to live with herself now that she’s no longer a teenager. The flashbacks happen as interruptions in the narrative, mainly because that’s how they occur in real life, whether through the unconscious or conscious. Until we can accept our past misdeeds, we’ll all be haunted by them, so Jodi’s story, in many ways, is about her learning to forgive herself.

PM: The female relationships in this book are as intimate as they are fraught with insecurities and deception. Jodi’s friendships with Isla, with Monika, with Alex, and later within ‘the circle’ — each of these offer a multifaceted power dynamic. How do the interactions in your book reflect or contradict your own views about female friendships?

JDD: Although there are some lofty ideas in the novel–the split between figurative vs. abstract art, what it means to be an artist in a decade of consumerism and greed, how we define beauty–at its core, the book is a series of female friendships. None of these relationships are easy or clear cut. There are betrayals and lies, feelings of anger, jealousy, competition, along with intense longings for companionship, love, and partisanship.

As a woman who writes about relationships (mostly romantic relationships in my sex column ) I wanted to write about the power of female relationships, and how vital they are to women leading fulfilling lives. In my own life, my female friends–from my sister, who is my dearest love, to an intimate circle of close friends, to an even broader circle of female colleagues and acquaintances–are extremely important to me. I couldn’t imagine my life without them. That said, these relationships aren’t perfect, but they defy the notion we see in the media about “catfights” and “back-stabbing” women. This is not my reality, and in the end, with Jodi, and her best friend Monika, we see a true friendship that, while it may be difficult, represents two women who care and support one another.

PM: Throughout the book, the character of Monika often encourages Jodi by insisting that she is a ‘real’ artist. Amid the glamor and politics of the art scene, there is the tension posed between what is real, and what is inauthentic or false. We see Jodi come to terms with ‘recognition factor’ and all that implies. What, in your mind, constitutes artistic integrity? What is the relationship between compromise and ambition?

JDD: Well, there’s a fine line between ambition and recklessness. The desire for what I, or rather, art critic of the 1980s, Rene Ricard, calls “the recognition factor,” is huge for any artist. After all, we’re not making art in a vacuum and there’s no greater desire for an artist to actually earn a living by making one’s art. So how do you not compromise your artistic integrity? I think artist Jules Kim sums it up with this video she’s made on the subject–it’s all about being transparent about your process, vision, and product.

PM: Sex seems both a reductive and empowering force in Jodi’s life, and it informs her growth as a woman and as an artist. How has sex and sexuality, at different points in your creative and working life, constrained or limited you? In what ways has it expanded your perspective?

JDD: Sex, ah yes, one of my favorite topics. I write about it all the time as a columnist, and in this novel, clearly. Why do I write about it? I guess because so much of it is a mystery, and because we’re told to hush about it–that sex is taboo–but at the same time, the media, institutional ideals about masculinity and femininity, and billion dollar industries will inundate us with “sexy” images to arouse us into buying commercial goods. This hypocrisy drives me crazy, both as a woman and consumer, not to mention as a writer who gets slammed in some of the Huffington Post message boards on my articles where I write frankly and reflectively about sex.

I am going to tell you a secret: I love sex! (Oh my god!) Sex is one of the times in our over calculated, negotiated, public lives where we get to be completely primal and honest, vulnerable and powerful. There’s myriad ways of having sex (and I don’t mean positions, I mean types of sex) and no one will ever be able to control that. So, really, we should accept that fact, and be open about our discourse on it. I think the world would be a better place if we could embrace ourselves for who we are–and part of who we are includes living as sexual beings.

…

Jill Di Donato holds an MFA from Columbia University, where she’s also taught writing, and is currently an adjunct professor of English at The Fashion Institute of Technology. She writes about sexual politics for Huffington Post, and as a sex columnist she’s contributed to TED Talks, FUSE, Refinery29, as well as broadcasts for the Huffington Post’s live channel. Her work has appeared in numerous literary journals and magazines, and her most recent project is a nonfiction book called 52 Weeks of Sex. Beautiful Garbage is her debut novel.

Paula Mendoza has an MFA from the University of Michigan, and her work has appeared in The Awl, PANK, The Offending Adam, and elsewhere. She lives and writes in Austin, Texas.

1 comment

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here. The sketch is attractive, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an shakiness over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again since exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this increase.