In January, frightened students in Maryland told a guidance counselor that two of their classmates had pointed guns at them. In February, a student in Virginia found a gun in a classmate’s backpack and alerted her teacher. Last week, a student in Massachusetts brought a gun onto a school bus and brandished it in front of his friends. These incidents would be traumatic, terrifying and troubling–if any of the weapons had been real. Instead, the real tragedy is how situations involving school children with pretend/imaginary weapons have been handled.

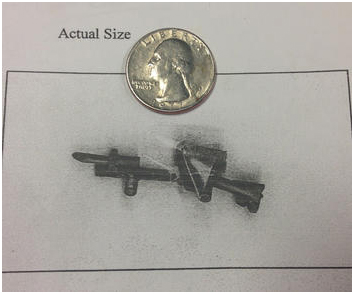

In the Massachusetts episode, a six-year-old boy boarded his school bus, eager to show his friend a one-inch toy gun that went with an action figure he had. The friend told the bus driver that his seatmate had a gun, and the driver took it from him. That appeared to be the end of the issue, until the bus driver made a call to the school office announcing she had confiscated a gun on the bus. Not surprisingly, hearing that a child had brought a gun onto a school bus sparked a brief panic, and the assistant principal immediately boarded the bus upon its arrival. The driver informed the administrator that the gun was a toy and that she had handled the situation, telling the children not to bring such toys on the bus. According to the child’s mother, he had to write a letter of apology and was threatened with detention as well as having his bus privileges suspended. School officials mailed a letter to parents informing them that their children were never in danger, attaching a photo of the toy gun alongside a coin to give parents an idea of how small the weapon was.

The incident in Virginia involved a larger weapon, to be sure, but a toy one nevertheless. The ten-year-old boy at the center of the story brought an orange-tipped toy gun to school with him in his backpack. A girl in his class discovered the gun and reported it, later telling her parents she was frightened by the toy. An email was sent out to the school community and according to the boy’s mother, parents thought her son “had a real gun in there and he was waving it around and ready to kill the whole school”. Despite the revelation that the weapon in question was not real, the child was not only suspended from school but also arrested, taken to court, questioned, photographed and fingerprinted, and has an upcoming hearing scheduled. The fifth grader also has appointments scheduled with a probation officer. A police department spokesman concedes that the response came before all of the details were known, stating “If we were able to investigate right away, the outcome might have been different.”

A game of cops and robbers led to the suspension of two six-year-olds in Maryland this past January. As the boys were playing, they made guns with their fingers and pretended to shoot at one another. Earlier that same month, a six-year-old was suspended from a neighboring school for making a finger gun. That child’s parents appealed the decision and the suspension was overturned. Of the case, child psychologist Dr. Joe Kaine noted, “I do not believe maliciousness was involved”. The doctor went on to say that at such a young age, most children’s minds are not capable of understanding why their idea of fun might make adults upset.

Legos only hurt when you step on them

That’s precisely the point, and the problem with the way toy/imaginary weapons are treated in most schools today. As a teacher, I have had students bring toy guns to school or use their fingers as imaginary guns, and I can’t begin to count the number of times Legos, Play-Do and construction paper have been turned into guns in my classrooms over the years. I have never suspended a student or sent him or her to the principal. Instead, I tell the child who brings a toy gun/squirt gun, “You cannot bring this toy to school. It is against our rules. If you are allowed to have it at home, that’s fine, but not at school. I’ll keep it until it’s time to go home.” If children build guns out of materials in the room, I tell them to take them apart or throw them away, and that we have a rule that we cannot make weapons at school. If they are making “gun fingers”, I tell them that they need to stop because we aren’t allowed to do that at school. I don’t tell them weapons are bad or evil or that pretending to have a weapon makes them bad kids. I just tell them that they cannot make those choices at school. Our handbook is clear that anyone who brings a firearm to school will be suspended (the term “firearm” includes any weapon designed to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive); squirt guns and Legos are not weapons and thus the students do not need to be punished, just reminded of the rules and expectations at school.

They’re kids, not criminals

My own son was sent to see the principal twice when he was in kindergarten. There had been issues with children play fighting on the playground at recess. First, children played cops and robbers and pretended to have guns. After being told to stop brandishing finger guns, the children complied–and began pretending to shoot arrows from imaginary bows. They were told to stop, and they did–they switched to having pretend light saber battles. That’s the thing. Kids are kids. They learn through play, they express themselves through play, they resolve conflict through play, and they burn off energy and aggression through play. We wonder why so many kids are considered hyperactive or inattentive and yet any time they try to work that energy out on the playground they are told they’re doing it wrong. For the record my menace of a son was just recommended for the advanced academic program at his school this year, so pretending to use weapons hasn’t ruined his life.

Instead of calling in the National Guard when a child bites his Pop-Tart into a gun, parents, schools, and communities should focus on helping kids understand that school is simply not the place for pretend weapons and play fighting. As Larry Amerson, president of the National Sheriffs’ Association says, “we can protect our schools while refusing to let those who do bad things take away the innocence of children.” When kids inevitably do cross that line–because most kids test boundaries and because sometimes they just get excited and forget the rules–instead of sentencing them to public shaming must clearly, consistently explain the need to honor the rules and expectations of the school setting. No more, no less.