It’s so easy to go about our lives and assume we understand democracy and our capabilities as citizens in the United States. But chances are we all need to be a bit more informed about civics—and why it’s crucial to our nation.

“Well, Doctor, what have we got — a Republic or a Monarchy?

“A Republic, if you can keep it.” — Benjamin Franklin

If you were lucky enough to have a civics class in middle school, you probably learned a straightforward story about how our representative democracy works. The story I heard went something like this:

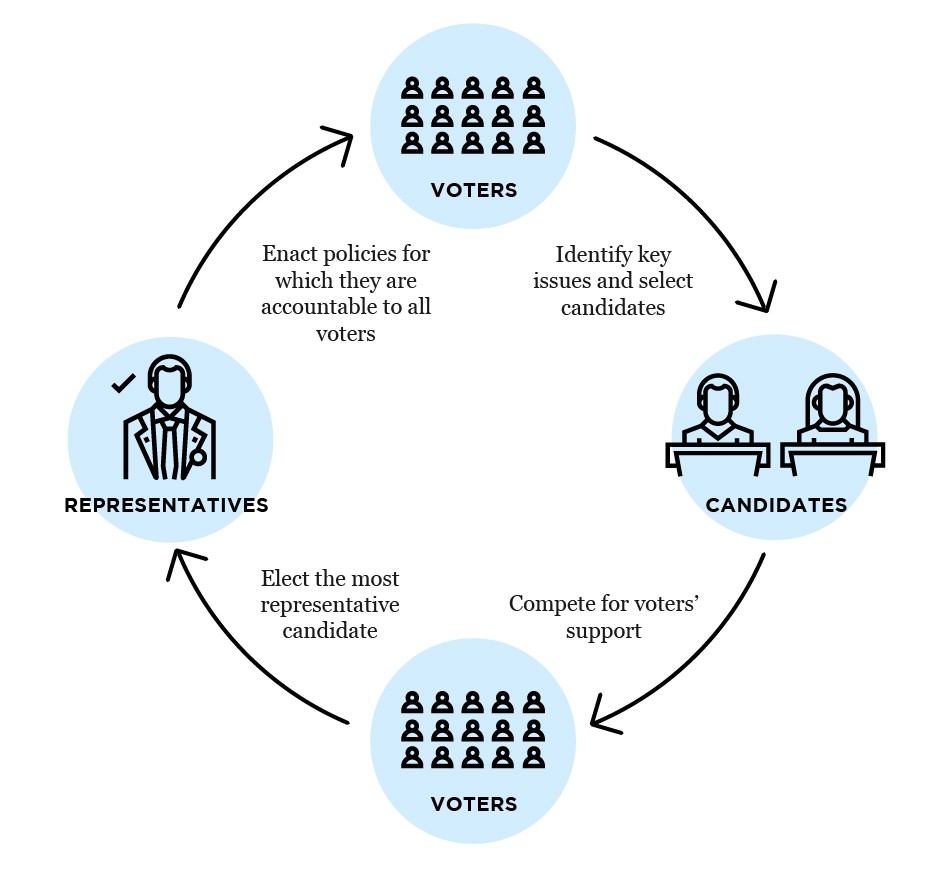

Citizens assemble in the public square to discuss and debate the issues of the day. From among the people, candidates step forward and vie for support through more discussion and debate. Elections are held in which voters select and thereby delegate certain powers to the most representative candidate. Representatives discuss and debate issues in public and make decisions in office that become policy that affects people’s lives and is the basis upon which representatives’ performance is evaluated. Representatives are directly accountable to their constituents via regular and open elections. Thus, our government is an open, transparent and accountable vehicle for people to collectively make and execute decisions through representatives who act on their behalf, tackling problems they cannot address individually.

Theory vs. Practice

In this model, citizens who exercise their right to vote are the ultimate source of power. They hold opinions and preferences, which candidates may try to shape but must ultimately reflect. They temporarily delegate power to representatives for a set period of time. They assess the job those representatives have done and how well those representatives continue to reflect their current opinions and preferences. And they ultimately decide which representatives keep their jobs and which do not.

In short, voters’ participation in the political process creates a feedback loop between the governed and those who govern with their consent. When this feedback loop is working, it regulates the system to align representatives’ actions with the interests of the electorate:

Image by Nate Clancy

Courtesy of Matthew Mahan

This is a beautiful vision, and I’m sure that there have been people and places in the U.S. for which representative democracy has more or less achieved it (e.g. white, landholding men in 18th century New England towns; perhaps your neighborhood association today).

However, our representative democracy doesn’t seem to follow this model in most cases today.

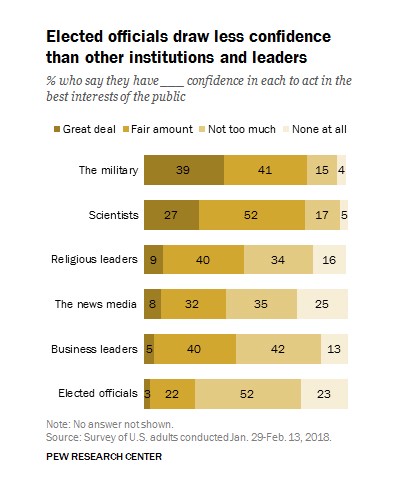

Importantly, most Americans simply don’t believe their democracy works this way. Pew and Gallup have examined this question from many angles over the years, consistently finding low public trust in government and lack of faith in elected officials. In its most recent study, Pew found that only 3% of Americans have a “great deal” of confidence that elected officials act in the best interests of the public, ranking worse than members of every other major institution they tested. Fully three-quarters of Americans expressed low confidence in elected officials’ motivations:

Even if one wants to argue that public perception is misplaced (to be clear, I don’t think it is), the actual process of electioneering in the U.S. belies the ideal narrative we tell ourselves in civics classrooms across the country. Personally, I’ve worked on enough political campaigns to know that there’s more to this story.

The “Money Primary”

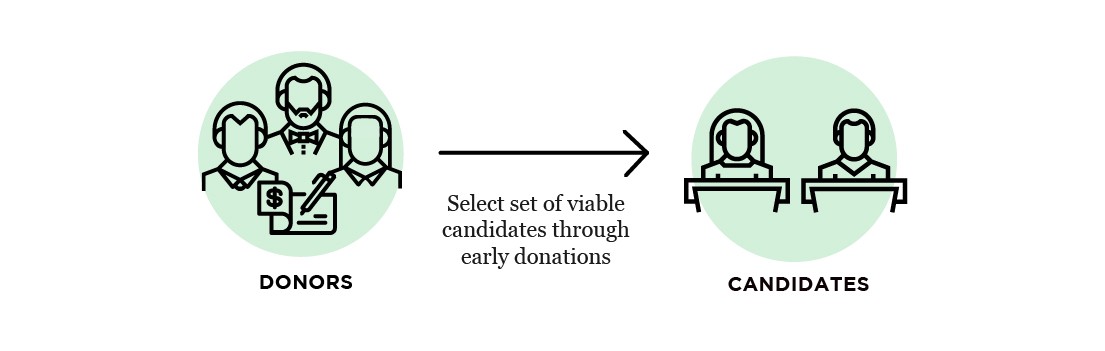

First, in practice, elections start long before even the most active voters are engaged. Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig has written about the “money primary” that takes place before the voter primary and during which wealthy donors determine candidates’ viability through their campaign contributions. These early contributions disproportionately shape elections by providing the first signal of viability to media outlets and endorsing organizations, who tend to amplify the signal, and by determining whose message reaches voters at all.

Given this dynamic, candidates spend an inordinate amount of time with donors who are willing and able to write these large early checks — be it a billionaire, union boss or corporate executive. The average member of Congress spends somewhere between 25% and 75% of his or her time in office fundraising from donors, according to reports that have attempted to estimate this figure. In a 60 Minutes exposé released in 2016, Congressman Rick Nolan stated that both parties tell new members to target 30 hours per week of call time with donors. In any case, fundraising and its concomitant relationship-building is a significant focus for any candidate.

Unfortunately, political giving is extremely concentrated. “Large-dollar” donors — those giving over $200 to one or more candidates per cycle — make up only 0.4% of the adult population, yet account for over two-thirds of all campaign funding. This means that fewer than 1 in every 200 people in the U.S. are responsible for contributing the vast majority of the dollars that drive election outcomes that affect everyone. And while raising the most money does not guarantee a candidate’s success — especially when two or more candidates are well-funded and competing for an open seat — raising a lot of money is almost always the price of admission.

Donor influence represents the first major challenge to the story we tell in 7th grade civics: in practice, a tiny subset of relatively wealthy citizens — not average voters — significantly narrow the field of viable candidates and often have a decisive impact on the final outcome of a race. Unlike the loop presented above, it is more accurate to say that influence in real-world elections originates with donors, who play an outsized role in the selection of candidates:

Image by Nate Clancy.

Courtesy of Matthew Mahan.

This means that candidates not only spend more time with donors than average constituents, but they also have to be more finely attuned to the needs of their donors. Donors, after all, have the ability to sink a campaign before it gets out of the gate.

Converting Cash into Votes

Candidates, in turn, use campaign funds to advertise themselves to voters, who often lack accessible and trustworthy alternative sources of information about the race. This is especially true for the 99.9% of elections that happen at the state and local level (only 538 out of the approximately 520,000 elected offices in the U.S. are federal-level offices), where newspaper staffing has declined 40% over the last twenty years.

Unfortunately, when candidates advertise themselves and by extension, the election, they don’t bother to reach out to most voters. To win, candidates only need the support of 50% of the voters who will cast a vote for their office. Moreover, since most federal and state-level districts are sufficiently and unevenly polarized (if not also gerrymandered) to be “safe” for one party in the general election, candidates often only need the support of 50% of the voters who will cast a vote in the primary election for their office.

This number tends to be extremely low. In Presidential years, when media attention is high, state primaries typically have turnout rates between 15% and 35% (and much lower for caucuses). Turnout measures how many people cast a ballot at all, but “drop off” from the top of the ticket to the bottom can be greater than 50%, meaning that actual turnout for lower offices in a primary can easily reach single-digit levels. In midterm years, these figures are even lower, often half as much again. For example, in 2012, Senator Ted Cruz managed to win his GOP primary in the safe red state of Texas with the votes of just 4% of the voting-eligible population!

Low turnout, plus inherently limited time and money, incentivizes candidates to advertise to the narrow slice of voters who are A) most likely to turn out and B) already mostly aligned with their values. In most races, and especially primaries, this means targeting older, whiter and more ideologically extreme voters and often aiming to activate their fear to boost turnout. Rather than engage and enlighten the broader electorate, political advertising tends to reinforce the shallow participation of a small, ideologically extreme set of voters.

Targeted advertising represents a second major challenge to my 7th grade civics lesson. In the absence of other engagement channels, candidates use targeted advertising to identify, “inform,” and turn out their narrow base of voters. Many of these voters are “low information,” meaning they don’t possess deep knowledge of the office in question, the field of candidates or the policy decisions facing them. Therefore, their decisions often hinge on superficial factors like party affiliation, name recognition and perhaps a candidate’s message on one or two hot button issues — each of which paid advertising can meaningfully move.

Democracy Disrupted

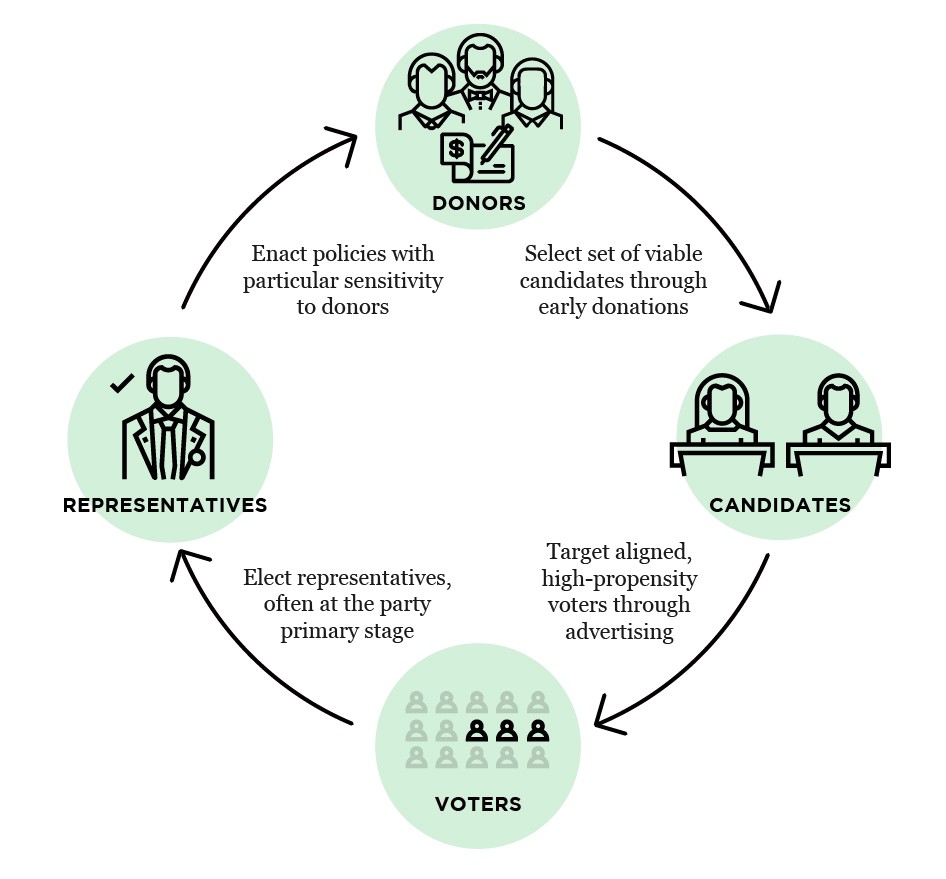

These two fundamental challenges — the centrality of money in campaigns and the use of that money on targeted advertising as the primary means of engaging voters — disrupts the feedback loop imagined in the original story about our democracy:

Image by Nate Clancy.

Courtesy of Matthew Mahan.

In the first version of the story, voters selected winning candidates, winning candidates selected policies, and elections kept winning candidates accountable for selecting policies that benefited most voters. In the second, and I think more accurate version of the story, donors drive candidate selection, candidates select and mobilize small subsets of voters in low-turnout elections, and elections often become low-substance marketing battles largely divorced from the actual policy decisions and campaign contributions that make the system go.

In this second version of the story, the feedback loop between donors and candidates inevitably rivals the feedback loop between voters and candidates. Candidates who want to win elections must position themselves to secure enough funding to run a modern campaign. While their stated beliefs on a few prominent issues must be roughly in line with a majority of their primary voters, their more granular policy positions and the bulk of their work in office must be responsive to the — often very specific and narrow — interests of their biggest donors.

There is a great deal at stake between the first and the second story of how influence flows in our representative democracy.

At a policy level, the second story calls into question how representative our representative democracy actually is. Can a representative whose job hinges on the support of one-half of one-percent of her constituents faithfully legislate on behalf of the other ninety nine and one-half percent? Can a society that is replete with small but powerful interest groups that directly profit from the status quo make the kinds of difficult policy choices our nation’s long-term health requires?

At a systemic level, the second story calls into question the long-term viability of our form of government. How long can a representative democracy survive when a majority of its citizens no longer believe that their representatives act on their behalf?

Who’s in Charge Here?

It’s tempting to blame greedy donors and spineless representatives for corrupting our democracy. Indeed, many popular narratives on both ends of our political spectrum do just that. Whether the culprit is corporations, unions or the media, the overarching political narrative of our time on the Right and the Left argues that self-interested actors have undermined the legitimacy of our government by capturing it for their personal gain.

But such claims misdiagnose the root cause of our democratic malaise. In the ominous quote at the beginning of this post, Benjamin Franklin warns that our democracy’s very existence relies on our active maintenance. He and our other political forebearers designed a political system that assumes a highly informed and engaged citizenry whose consistent participation creates feedback loops between representatives’ decisions and their reelection prospects. Instead, too many of us have ceded the public square to smaller and better organized interests who have turned this electoral feedback loop to their narrow advantage.

In a sense, large-dollar donors have hacked our democracy. Their money affords them disproportionate access and influence. It is right to fight their unfair advantage in the system. But it is even more important to recognize that this hack has been made possible because we have collectively introduced a vulnerability into the system. The entire logic of representative democracy begins to break down when large numbers of us disengage.

This is what my 7th-grade civics class got wrong, or at least failed to acknowledge had gone wrong in our modern democracy: durable systems of human interaction contain feedback loops that incent each of the actors in the system to engage in ways that preserve the overall health of the system. When these feedback loops break down, the actors shift their behavior accordingly and with the potential to threaten the entire system’s stability. I believe we are witnessing this kind of instability — a crisis of trust — in our politics today.

The key question then — for the majority of us who are dissatisfied with the state of our representative democracy and concerned about the long-term implications — is how to broaden and deepen voter engagement to jump-start these feedback loops and better align representatives’ actions with the public interest.

Originally published on Medium.

By: Matthew Mahan, CEO of Brigade