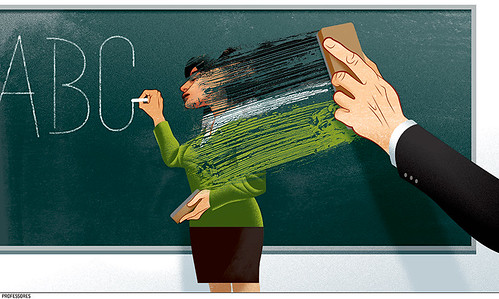

The United States is currently experiencing a teacher shortage-a far cry from a few years ago when the economy forced many districts to issue pink slips to teachers in order to cut costs. According to a recent New York Times piece, the number of college students entering teacher prep programs has dropped by thirty percent in the past five years. In California, the number is a startling fifty-five percent. Many districts across the country are scrambling to find teachers, some hiring unlicensed teachers with an understanding that they will complete licensure programs while on the job. Where have they gone? For the most part, they’ve gone into the private sector, where salaries are more in line with college grads’ expectations and qualifications. Still, money isn’t everything, and it doesn’t answer the question–why? Why are young people choosing other careers and why are current teachers leaving the field long before retirement? A retired teacher gave some reasons in a blog featured in the Huffington Post. Among her concerns: “Too many of today’s politicians and corporate leaders talk about the poor quality of teachers without having any idea of what they are talking about….Teachers’ voices are not heard enough nor sufficiently requested when it comes time for decision-making…Too many teachers are “evaluated” on the basisof statewide tests in their classes.” Global news agency AJ+ recently interviewed teachers to find out what challenges they faced and what concerns they had that might lead some to leave the profession. They compiled these interviews into a video.

As a teacher, much that I’ve read and seen resonates. I’ve seen it in my own school and heard it from teachers in neighboring districts. From my experience and the experience of colleagues, there is one issue overshadowing the rest when it comes to teacher burnout, and influencing the choices of would-be teachers–Assessment Overload and the Curricular Chaos that comes with it.

Kids are being tested more than ever before. Call it an assessment, skill measurement, evaluation–bottom line, it means more testing. There are a few different reasons for this. One, there is an increase in pressure for states and districts to “hold teachers accountable” for student learning. How does one determine if someone is a “good” teacher? The most streamlined, user-friendly way for evaluators is assessment. You have the teacher test the children, look at the scores, and the teachers with high-scoring classes are clearly the best teachers, right? I mean, sure, the socioeconomic level of the students doesn’t matter; it doesn’t matter if they are hungry because there’s not enough food at home, or traumatized because they saw mom hit dad that morning or because a sibling molested them the night before; it doesn’t matter if they were absent twelve days that semester; just give all of the kids the same test with the same questions and the highest-scoring classrooms have the best teachers, right? Wrong. That’s not how any of this works. The performance of any one child on any given day isn’t a measure of the whole child, nor is it a measure of a teacher’s worth. Yet this is the standard for determining who is “succeeding” in the classroom.

Another reason for assessment is that money is tied to curriculum which is tied to assessment. Sounds confusing? Let me explain. Race to the Top is a grant program that gives money to school districts. Yay! Free money! Sounds great, right? Except it isn’t, because nothing is ever really “free”. If you want the money, you have to implement some things, namely, Common Core State Standards, which is a misnomer because they are federal standards that just happen to have “State” in the name because hey that makes it sound like states choose, right? I suppose technically they choose, but the choice tends to boil down to, “Do you want this big pile of money AND our standards, or freedom to use your own standards and NO pile of money?” So if you had to choose between a lot of money or no money, and all you had to do was implement some standards, you’d take the money, right?

We’ve been here before, not so long ago, with No Child Left Behind. NCLB required states to adopt standards and test students each year to gauge their progress. Fearful of losing federal funds, all fifty states got on board, testing every student, every year in every grade from 3—8 as well as in high school. Fun fact: Prior to NCLB, only 19 states tested every kid every year. Amazing what a little money and pressure can do. A school district in Florida voted to opt out of the state’s mandated tests tied to the Common Core State Standards due to concerns about the excessive testing of students, but the vote was later rescinded amidst concerns the decision would leave the district in violation of state law and risk losing funding.

And now so it is with Common Core and similar initiatives. Teachers are pushed to the limit as they struggle to implement new standards and new curriculums. This pressure is felt most intensely by elementary teachers, because they teach all subjects every day. Let me repeat that. All subjects. Every day. If you’re a math teacher you have a new curriculum to implement every 5-6 years, on average. You roll with it, adjust for a year or so, and move on. If you teach in elementary grades, you adopt the new math curriculum, and as you’re trying to figure it out you get a new language arts curriculum. And then science, and social studies, and a new handwriting program, and…and…and. And by the time you’ve gotten the hang of a couple of them, a new initiative comes along and you get to do it all over again.

Of course, you don’t just get the new curriculums and standards, you get the new assessments-because how do we know you’re executing the new standards well unless we test, test, test the kiddos in your charge? I know districts where the kids are assessed within the first few weeks of school. First few weeks. You know, the adjustment period, the time where we’ve all been told kids are finding their feet again after summer break and working their way back up to where they left off last May? Yep, they’re getting assessed, and then they get to be placed on lists according to their scores. Any student who falls below the dreaded “red line” of expected test scores must be given intervention for a set amount of minutes each week–this intervention being provided by that same classroom teacher who has no associate/aide to help her and must keep teaching everyone else everything else while also providing interventions–and must be reevaluated every few weeks to gauge progress. If progress isn’t hitting the desired aim line, guess what? The teacher has to gets to provide more intervention for each child, on top of teaching everyone else everything else. And of course these assessments and interventions have to be tracked–everything must be tracked!–so that the Department of Education can monitor and make sure teachers are “doing a good job”. Kids as young as four are having test results uploaded into a database so the Department of Education can see how they’re progressing. Last year I heard one of our school’s happiest, bubbliest, most upbeat teachers let out a sigh of defeat and proclaim, “I’ve gone from teaching to managing. I spend so much time managing information that used to be time spent teaching.”

Somebody needs to call a time out. But who, and how? As long as the Department of Education continues to tie new initiatives to funding, and in turn to assessment, this will continue. As long as people who’ve never worked a day inside a classroom insist that “the test’s the thing” in evaluating teacher performance, this will continue–unfortunately, so will the mass exodus of good teachers and the decline in young people choosing teaching for their future profession.