Photoshopping is an insidious practice with real consequences and measurable effects. The photoshopping of bodies that promotes unrealistic standards constitutes false advertising and goes further to constitute an egregious social harm. It must be regulated. The scope of the problem merits action, and it is the Federal Trade Commission’s obligation to intervene and protect consumers from this threat.

Photoshopping refers to the altering of images in advertisements, but the practice today goes far beyond mere edits. Many have taken individual liberty to expose prominent examples, from Keira Knightley’s altered bust in a movie ad to Lorde’s modified nose.

There are countless other examples that prove excessive photoshopping by companies that use models or public figures to sell their products. It is natural and acceptable to expect advertisers to make their product look the best it can. But there is a difference between the enhancement of a product and that of a person – the routine transformation of real people into people whose features do not actually exist. It is one thing to airbrush a woman’s pores and another entirely to give her a hip to waist ratio that is not only unrealistic, but nearly impossible without plastic surgery. This is false advertising, it is sexist toward women and men and it is undeniably harmful.

The connection between unhealthy images and a host of unhealthy practices is clear. Men are taught hyper-masculinized beliefs through images that make brute strength out to be the highest aspiration of masculine men. Male consumers are made to think that they have to look like superheroes with 8-pack abs, and the blind emphasis on muscle mass insinuates that toughness is what makes men worthy. It is this to be seen as worthy, as masculine enough, that leads to many social problems like the disparately high proportion of boys kicked out of school and low proportion enrolled in secondary education and the male propensity to commit violent crimes and abuse drugs. Advertising that targets men reinforces an unproductive expectation that insists on the demonstration of masculinity no matter the cost.

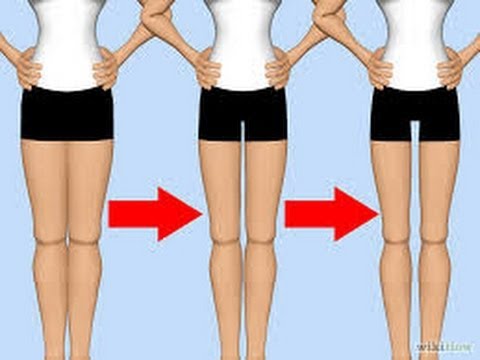

Women are taught to concentrate on their appearance: spend more money on beauty products with the hopes of growing impossibly long eyelashes, be more concerned about achieving an impossibly toned stomach or an impossibly small waist. The latest trend in female photoshopping is particularly contemptible. I can’t peruse a store’s website these days without dozens of photoshopped “thigh gaps.” A thigh gap is the space between a woman’s thighs. Bone structure determines whether or not this space exists, but images are now routinely photoshopped to give models thigh gaps and promote the expectation that women should naturally have one, despite its blatant invention. The fact that the norm in advertising is now the practice of chopping off a woman’s vagina to make it seem like she has a thigh gap, most notably in Target’s photoshop failure, is symbolic of a trend that disrespects the consumers being fed these advertisements.

The consumption of these images and their messages doesn’t just influence the malleable process of attraction. It causes self-esteem issues like self-objectification and body checking, as well as fatal eating disorders. 20 million women and 10 million men in the U.S. suffer from eating disorders. The solution to this problem is reasonable regulation. Advertisement should not preclude a basic level of social responsibility; companies should not pretend like certain features are normal, natural or possible.

While it may be unfair to promote a very specific beauty ideal, it should not necessarily be illegal. What should be illegal is projecting standards outside of a healthy or possible range. Israel, motivated by an alarmingly high rate of eating disorders that are the leading cause of young death, has adopted a policy that bans malnourished models or photoshopping that makes models appear underweight. The UK banned an Urban Outfitters ad of a model that would be classified as significantly underweight. This isn’t a matter of free speech or right to work but of consumer protection. The status quo today is a highly unprotected population of consumers.

You don’t have to think all ads should promote realism or a certain body standard. But we should all agree that participating in a world of fiction — body parts that don’t exist — should at the very least necessitate FTC oversight, the kind of oversight it neglected to take on in 2011 or 2014 when it merely proposed laws advocating more research. This goes beyond the propagation of women in the media as sexual objects. This is a systematic affront on consumer health, and the introduction of protective, not paternalistic, policies should no longer be up for debate.

By: Caitie Karasik . This post originally appeared in the Stanford Daily. Contact Caitie Karasik at ckarasik ‘at’ stanford.edu.