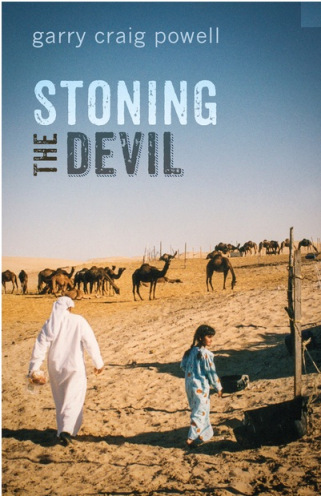

Garry Craig Powell’s Stoning The Devil interweaves narratives of sex, power and identity through a feminist lens, with all of the contradictions and myriad facets that perspective affords. This episodic novel–each chapter of which is complete unto itself–is first and foremost a work of lush and vivid prose. Various formal innovations, from the epistolary opening chapter to the syntactic feat of the chapter entitled “Sentence,” demonstrate Powell’s technical virtuosity. It’s this skill that allows him to capture the Gulf landscape’s severe beauty, alongside a wealthy city’s urban sheen and excess, with clarity that feels neither detached nor heavy-handed. While the Gulf in general, and the UAE in particular, almost function as their own characters in the book, it’s those souls who suffer and thrive in the foreground whom Powell trains his, and in turn the readers’, attention on. The characters which inhabit Stoning ’s pages are sensitively drawn and attuned readers will find themselves quickly invested in the lives of Badria, Fayruz, Alia and all the other “players” of this novel.

Even now as I write this, weeks after reading this book, I am still haunted by the story and the traumas that befall Badria, and Fayruz–two characters who seemed to me to embody traditional Western feminist ideals of power. Badria’s voice is the first we encounter and her spirit and ferocity, as much as her unsettling personal account of rape, makes her an urgent and powerful narrative force. We learn of her pilgrimage to Mecca and read of her burgeoning feminism and political awareness. Closing a letter to her cousin, she writes:

“Why must men submit to the will of men? Because the Holy Qur’an tells us to. And who wrote the Holy Qu’ran? Men, that’s who. Arab men.”

Badria returns in the stories of other characters and we observe how trauma shapes her life and guides her interactions. It’s not unusual for a book to forego plot in favor of personal stories, but these vignettes are unique in how the overlapping relationships, within such a small space, work to reveal and sharpen each character. Badria’s brother Sultan is one of a handful of male characters in this book, and its by way of the flattened-out qualities of his menace and sadism, which presents a kind of distorted mirror image of Badria’s own mean streak. The siblings share a common trait in cruelty and it’s fascinating to read the ways in which Powell distinguishes and inflects the nature of each.

Fayruz, Palestinian refugee and wife of a British ex-pat aid worker, is a sexually liberated, liberal-minded and independent woman by Western standards. In the chapter where she first appears, she calls out her lover, Colin, on his impractical romanticism, all but accusing him of a privileged and coddled existence, saying things like, “You can’t face the boredom, the mediocrity, the ugliness of your existence” and, “You are only interested in glamour, this stupid Hollywood love. You are a child.” Her steely pragmatism is fashioned by a life lived through and within violence and hers is a complicated strength. Colin describes her in a later chapter as a challenging beauty:

“He never met anyone like the thin solemn girl whose tongue stung like a scorpion. She invariably carried a book by Kahlil Gibran, or Ghassan Kanafani, and was, he imagined, deep.”

His disillusionment over the depth he imagined he saw in Fayruz betrays his own superficiality. In this same chapter, Fayruz charges him with something more damning than a sense of entitlement and romanticism and asks a question that crystalizes a crux this novel pivots on: “And what about the Arab body? … Does that only understand force as well?” The Arab body, here, gestures to all bodies oppressed, threatened and feared.

As we move through these stories, we are confronted with the sometimes discomfiting implications inherent in any ideal. At one point in the novel, Powell’s insight into the female plight offers a moment wherein Fayruz contemplates what Colin means to her: “She needed to retain her sexual sway over him. It was the only power she still had, the only means she knew of asserting herself.” So, Powell arrives at that longstanding myth which all women, regardless of culture and intelligence, inherit and struggle to unlearn. I came away from reading this book with deeper questions to trouble over than when I began, the possible answers and implications of which I’ve spent my time since discussing with anyone who has cared to indulge me. What is power if it is contingent upon man’s apparent surrender? And what true gain is it if the power he gives up is yet just one more assertion of a different kind of power–that of brute force and ownership?

Stoning The Devil does not shy away from controversy, nor does it provoke for provocation’s sake. Barbarities and hypocrisies of both Islamic and Western cultures find their complexity–in these stories as in real life–through the individual human being. Powell’s sensibility, as well as sensitivity to loaded imperialist rhetoric and post-colonial politics, offers some truly inspired and nuanced passages that work within that charged linguistic space to fret the limitations of “enlightened” thinking. Powell plays with the practice of exoticizing, in small and profound ways, but what is ultimately gratifying here is that what we’re left with are not just concepts or too-easy epiphanies, but real people, written with a skeptic’s compassion and a poet’s clarity.

By Paula Mendoza